Thursday, December 25, 2008

Undergraduate Events and Calls for Papers

We get periodic calls for undergraduate paper submissions for publication or prizes. I'm happy to post them when I get them.

+++++

Ephemeris Undergraduate Journal of Philosophy

Ephemeris is an undergraduate journal of philosophy published at Union College and student-run. The purpose of Ephemeris is to harvest exceptional undergraduate writing grounded in the distinct value and interest of the philosophical endeavor. Contributions are solicited in all areas of the philosophical discipline. Contributions should take the form of essay, article, or short note. Responses to previously published articles are also welcome. Be sure to include your name, postal and email addresses, and theuniversity or college in which you are enrolled as an undergraduate. Email: Please send your work to ephemeris-uc@gmail.com. Deadline for submissions March 2 2009. Please visit the website for further important details

<http://punzel.org/Ephemeris>

+++++

The Interlocutor: Sewanee Philosophical Review is pleased to announce its most recent volume and its first call for high quality undergraduate essays for its upcoming volume. Please send this announcement to students who might have an interest in this opportunity.

Our call for essays and instructions for submissions can be viewed at http://www.sewanee.edu/philosophy/interlocutor/submit.html.

The most recent volume is available at http://www.sewanee.edu/philosophy/interlocutor/journal.html.

If you or your students have questions, please feel free to contact interloc@sewanee.edu.

+++++

The Second Annual Southeast Philosophy Congress invites submissions from undergraduate and graduate students in any area of philosophy. The Congress, hosted by Clayton State University in Morrow, Georgia, runs February 13-14, 2009, with keynote speaker Jack Zupko from Emory University. Presented papers will be published in online and print proceedings.Talks run 20 minutes, followed by a 10 minute question/answer period. Please email papers, accompanied by a brief abstract, to Dr. Todd Janke: ToddJanke@Clayton.edu. Submission deadline is January 31, 2009. To allow time to plan travel, speakers will be notified immediately upon acceptance and selection will close when all slots are filled. The registration fee of $45.00 includes lunch both days and a print copy of the proceedings.

Monday, December 15, 2008

Ethics and Subjectivism

I just finished teaching Ethical Theory for the nth time, and this time I was struck by the (in)consistency of the finals I received. After going through several conceptions of ethics, I introduce my students to Logical Postivism, the critique of philosophy through the verificationist theory of meaning. On this view, a claim is meaning if and only if it is verifiable, i.e. if and only if there is some empirical test to determine if the claim is true or false. AJ Ayer defends this view and uses it to develop his own anti-ethical theory, namely that almost all claims in ethical theory are either non-verifiable nonsense, or empirical claims suitable more for psychology or sociology than ethical theory. The view Ayer ends with he refers to as "hyper-subjectivism," namely the view that "Theft is bad" expresses a subjective feeling, but makes no claim at all. It is like someone saying "ice cream, mmmmm" with all sorts of yummy sounds, which Ayer claims does not make any claim about ice cream, not even that I like it. Instead, it evinces a feeling.

Subjectivism is the view that the claim "x is good" means "I like x." It is properly an ethical theory. Such a theory makes criticism of ethical claims moot, since no one can show that someone else ought to like ice cream. It is just what they feel. There are many critiques of subjectivism, but that is not what I want to discuss.

Instead, on my finals, I ask my students to consider the critique and then answer the question of whether ethical theory is worth studying. If we only make nonsensical claims where there is no way of determining who is right, what is the point? Now in this particular class, the response was overwhelming: The all said Ayer was right, more or less, both that ethical theory was non-verfiable, and in his hyper subjectivist analysis of ethical claims. But they also all claimed that ethical theory was still worthwhile as an activity, pointing to how much they got out of the course, for example. Other than that, however, they argued passionately that there was no right answer to which ethical theory was correct, that each individual had to decide for themselves (on the basis of what, if Ayer is right, they did not say). At the same time, they said frequently that you can be either Kantian or Humean about ethics, since it is all subjective. But Kant or Hume's theory is not subjective. If either are right, the subjectivist is wrong, as is Ayer, since accoring to Ayer, Kant and Hume are being nonsensical.

So how can all these differing opinions fit? How is ethical theory worthwhile if ethical claims just say what you feel? How can you be a subjectivist and a Kantian? I think I know the answer.

Philosophers separate the theory from a "meta" theory. The words come from advanced logic, where Tarski overcame problems in theories of truth (like the liars paradox) by separating claims within a theory, and claims about a theory, similar to questions within a game, to questions about a game. According to Tarski, "Grass is green" is a statement within a language. But the claim "Grass is green is true" is properly a statement about a statement, and hence is properly written "The sentence "Grass is green" is true." Truth is a meta concept, part of a theory about theories. Armed with this view, he showed that the liar's paradox ("This sentence is false") is rooted in an ill formed sentence.

So now here is my thesis: My students may think Kant is right about ethics, or Hume is right, but they are subjectivists at a meta level. That is, they think which theory you adopt is a subjective choice, and hence there is no theoretical criteria for choosing which theory you adopt. Hence you are perfectly free to be a Humean as well. But within the theory, you are bound to its dictates. Ethical theory may then be worth while to spell out the details of each particular choice, but do not confuse that somehow getting to the truth. Within a framework, you can determine what is ethical, and what that means, but there is no outside framework to choose which theory to choose, since that is all a purely subjective matter of choice. So Ayer is right in part. Its not that ethical claims are nonsense. Within a framework, they make sense. What is nonsensical is to argue about which framework is right. And that was part of the non-sense Ayer objected to: arguing about things where there is no way of determining who is right.

I plan on taking this blog up again at the beginning of the next semester. Enjoy the break.

Wednesday, December 10, 2008

Thank you....

PS: Everyone make sure to tell Hanno how much you enjoyed his presentation. It was an acceptable alternative for a Friday Night.

- Mikey C and the Phurious Phive

Friday, December 5, 2008

New information regarding the planned philosophy major and minor (by MAB)

http://www.mcneese.edu/philosophy/majors.html

Tuesday, December 2, 2008

The Appeal of Existentialism

http://melancholicfeminista.blogspot.com/search?q=existentialism

Filmosophy: "Starship Troopers: The New Republic"

4:00 p.m. - 7:00 p.m.

Hardtner Hall, Room 128

Dr. Bulhof will present a discussion of Plato's conception of the Republic.

You can access the official poster here

Monday, December 1, 2008

The New Republic

In Starship Troopers, Paul Verhoeven shows a society split into three groups. We are shown the prosperous family of the main star, Rico. His family plan for him to attend Harvard, but Rico chooses instead to join the military. His family is in shock by his choice. They do not understand, and think he is making a foolish choice, throwing away his future. The wealth of the family show that the society as a whole is prosperous, for only prosperous societies can produce great wealth. The society also produces enough wealth to arm and train an army with the highest level of technology, and to fight a never ending war of expansion. There may well be poverty and misery, but we never see it. the point, however, is that the family represents a class of people driven by love of money, and the drive of the whole class creates the prosperity in the society. This mirrors Plato's conception that we read about last week.

The ends of the money lovers are different from the ends of the honor lovers. They want different things in life. What they place value upon are different as well. It comes as no surprise that the choices they make will be looked upon with contempt. the money lover cannot understand why the honor lover chooses a life path that promises only pain and sacrifice, and no luxuries. The honor lover, on the other hand, has nothing but contempt for the soft pleasures that drive the money lover. Those people cannot are self-centered, and cannot handle pain. Sacrifice has no meaning for them. This split is mirrored then in the movie as well, with one key difference. Rico enters the military not out of the love of honor, but the lust for a girl who enters the military. But in Boot camp, the martial spirited soldiers are separated from the ones who cannot handle it. While this separation is being made, the new soldiers are taught their craft, they are shaped to fight a military ethos. Plato spends much time in the republic describing the education which makes the best most virtuous soldiers. Boot camp is that in the film. By the end, the soldiers have a love of honor, sacrifice and display a certain kind of contempt for civilians. Now the soldiers recognize something more important than themselves, and are willing to die for it.

So we have in the movie a class split, between the military and the civilians, between the defenders of the society and its producers. And we have people whose natures determine to which part they belong, and an educational structure which develops those natures along the lines of virtue. In short, we have the Republic.

Now the the last class for Plato was the ruling class. These were people chosen from the military class who put the good of the community above anything else, even above their love of honor. In the movie, the ruling class comes from the military class as well. When the war goes badly, the leadership resigns, and new leadership is installed, new strategies are put in place. In short, wiser policies and policy makers are put into place. This, too, then matches the film.

For both Plato and Verhoeven, society is split into three distinct classes, each with different aims and desires, each content with their own lot in life, and each working in their own way for the good of the whole. The society works when each part does its part. The New Republic looks much like the Old Republic.

Monday, November 24, 2008

Plato's Republic

As part of my series setting up my talk on Dec. 5th, I will describe some key features of Plato's thought in his masterpiece, The Republic. Last time, we saw how Plato understood the origins of war and the need for an army. Earlier, he set up the origins of the state in the production of material goods and the need for the division of labor. The people who produce goods are allowed to become wealthy, but not to the extent that they cease to have a motive to work. The poor are allowed to be poor, but not to the extent that they become unable to work. Crafts will be mastered, and many will hire themselves out as wage laborers, those who do not or cannot master a craft. All of these people desire the luxuries of life, and as we saw, that desire has no limit. Using money as a symbol for this desire, the desire for money also having no limit, Plato calls these producers/consumers money-lovers. This group of people will be the largest part of the state.

The army is to be made of professional soldiers, in some sense volunteers. A good part of the beginning of the republic goes into the proper education of a soldier class. They need to be loyal to the people they defend, yet full of martial spirit towards the enemies of the state. For this group of people, to use the common expression, it is not the size of the dog in the fight that is important, but the size of the fight in the dog. The will to fight the right enemies is everything. Hence the education Plato conceives, the developing of the right habits, shapes those who will defend the state. These people do not seek wealth. They seek honor, and hence are called "honor-lovers." You do not need to reward them with money for a job well done, but with honor. Parades, medals and praise go a long way. Indeed, this can quickly reach contempt for those that value money above honor. Interestingly, as women have the same soul structures as men, Plato thinks women can love honor as well, and hence make excellent soldiers. In Plato's Republic, women are to be found as part of all three classes.

Some of the honor loving soldier class will show dedication to protecting the city above all else. From these, the leaders of the society will emerge. So the leaders come from the soldier class. Knowing what is in the interest of the society, who the enemies properly are, and how to accomplish the goals we might call wisdom. Wise leaders know what is best for the state. The key feature of the leaders is that they consistently and throughout their live put the good of the community above their own. Knowledge of that good will the essential to that task. Hence, the leaders will love wisdom as they love the society. It is the lovers of wisdom, then, that will lead the state, and develop wise laws and practices. Of course, the love of wisdom, in ancient Greek, is philos sophia, or philosophers.

Sunday, November 23, 2008

Pattern is Movement.....

It just deserves to die

When it becomes another stale cartoon

A close-minded, self-centered social club

Ideas don't matter, it's who you know

If the music's gotten boring

It's because of the people

Who want everyone to sound the same

Who drive bright people out

Of our so-called scene

'Til all that's left Is just a meaningless fad

Hardcore formulas are dogshit

Change and caring are what's real

Is this a state of mind

Or just another label

The joy and hope of an alternative

Have become its own cliche

A hairstyle's not a lifestyle

Imagine Sid Vicious at 35" - Dead Kennedys

I would have posted this as a comment, but I felt that Hanno should be forced to read it

- Mikey C

Saturday, November 22, 2008

The Movement is Officially Dead...And For Sale!

The sale will also feature such items as:

The Sex Pistols

A promotional poster for the 1977 Virgin Records' single God Save The Queen, designed by Jamie Reid. Opening bids: $2,000 - 3,000

For those of you who don't know:

Christie’s is the world's leading art business with global art sales in 2007 that totalled £3.1 billion/$6.3 billion. This marks the highest total in company and in art auction history. For the first half of 2008, art sales totalled £1.8 billion / $3.5 billion. Christie’s is a name and place that speaks of extraordinary art, unparalleled service and expertise, as well as international glamour. Founded in 1766 by James Christie, Christie's conducted the greatest auctions of the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries, and today remains a popular showcase for the unique and the beautiful. Christie’s offers over 600 sales annually in over 80 categories, including all areas of fine and decorative arts, jewellery, photographs, collectibles, wine, and more. Prices range from $200 to over $80 million. Christie’s has85 offices in 43 countries and 14 salerooms around the world including in London, New York, Los Angeles, Paris, Geneva, Milan, Amsterdam, Tel Aviv, Dubai, Hong Kong and Zurich. Most recently,Christie’s has led the market with expanded initiatives in emerging and new markets such as Russia,China, India and the United Arab Emirates, with successful sales and exhibitions in Beijing, Mumbai

Christie's will attempt to answer this age old question on November 24th, 2008: How much is a movement worth?

You can access the full press release here

You can access the Christie's site here

Wednesday, November 19, 2008

Upcoming Philosophy Conferences

At the last philosophy club meeting, several students expressed interest in attending a professional conference. The following conferences all accept students from undergraduates. In addition to attending, some of you may want to dust off your best philosophy paper and submit it for presentation. Here are some upcoming conferences of interest for students:

- Members of the LSU Philosophy department are currently planning an international conference on Mind, Metaphysics, Language, and Epistemology, to be held annually during Mardi Gras. Check this website for updates. Last year, the graduate students held a philosophy conference at LSU on April 11-12, 2008. I believe they are hosting the second annual conference in 2009.

- The thirty-third annual MidSouth Philosophy Conference is scheduled for Friday afternoon and Saturday, April 17-18, at The University of Memphis. Papers in any area are welcome. There will be a $20 registration fee, payable at the conference. This includes an undergraduate conference as well. Dr. Bulhof will be presenting at this conference.

- The University of Texas at Austin: 2009 Graduate Philosophy Conference: Experience, Judgement, and Action. A conference and workshop in contemporary philosophy: April 17-19, 2009.

The Second Annual Southeast Philosophy Congress invites submissions from undergraduate and graduate students in any area of philosophy. The Congress, hosted by Clayton State University in Morrow, GA, runs February 13-14, 2009, with keynote speaker Jack Zupko from Emory University. Presented papers will be published in online and print proceedings.

Talks should run 20 minutes, and will be followed by a 10 minute question/answer period. Please email papers, accompanied by a brief abstract, to Dr. Todd Janke: ToddJanke@Clayton.edu. Submission deadline is December 15, 2008. The registration fee of $45.00 includes lunch both days and a print copy of the proceedings.

Monday, November 17, 2008

War *huh!* What is it good for?

So I am working on my presentation for the MSU philosophy club's next installment of Filmosophy, where we take a movie and discuss its philosophical implications. The film I choose, with boggled looks to whomever I tell, is "Starship Trooper," directed by Paul Verhoeven. Yes, the movie about killing bugs. Really big ugly bugs. Lots of them. Certainly, no one expects much from Verhoeven. (Upon hearing of my talk, my little sister declared "I thought that it was truth universally acknowledged that Paul Verhoeven has the depth of a metaphysical and proverbial puddle." But, my dear sister, as Locke knew, there are no universally acknowledged truths, and he pointed to children and idiots as counterexamples. Be that as it may, and it may be...)

I will write a bit more about my talk next week and the week after (talk is Dec. 5th, called Starship Troopers: The New Republic), but there are side issues in the film that I wanted to address. I did not know, until I did a little research, that the movie was based on a book written in 1959. The book is quite different from the movie, and one of the key differences is its approach to war. The book was written by

Heinlein, a former graduate of the Naval Academy, and officer in the US Navy until forced out by health reasons. He left the Navy in the mid '30s. The book is also a clear reaction to the anti-militancy of the Left in the 30's and beyond. Three features to which I will point: 1) Heinlein seems to belive in the character building of boot camp. This is an extensive part of the movie, as selfish person gets transformed into citizen, where "a citizen accepts personal responsibility for the safety of the body politic, of which he is a member, defending it, if need be, with his life." The citizen puts the safety of the whole above her own. Combat and boot campe are the vehicles for this transformation. 2) War is a solution to problems, argues Heinlein. "Naked force has settled more issues in history than any other factor. The contrary opinion 'violence never solves anything' is wishful thinking at its worst." The radicals of the '60's were criticized for much the same view. No social advance, they argued ever came without violence. 40 hour work week, abolision of slavery, woman's sufferage, etc., etc. and 3) War is inherent in human society. The war with the bugs has no real beginning, and it is a constant struggle in the book.

Here the movie is quite different. On Verhoeven's interpretation, the humans start the war by moving into bug territory with the purpose of expansion. The bugs respond to human aggression by unleashing meteors that slam into the earth, and by wiping out the colonies.

Plato argued in the Republic that a state can either be healthy, and keep its needs to necessities, or it can give into its desires for more, limitless desires which are symbolized in the Republic as the love of money. This requires, eventually, seizing of the land of neighbors to feed our insatiable appetites. Our neighbors will want to seize our land, too, "if they too have surrendered themselves to the endless acquisition of money and have overstepped the limit of their necessities."(Rep. 373d) This in turn requires the formation of an army, both to defend the society and to agressively take from others. This, Plato writes, is the origin of war. "It comes from those same desires that are most of all responsible for the bad things that happen to cities and the individuals in them."(Rep. 373e)

War is not an essential feature of man, but an essential feature of man that has given into the insatiable desires of the luxourious life. War is not a good thing, but the creation of the worst elements in human nature. Human expansion into bug territory is thus a classic example of how Plato sees the origins of war.

Reactions?

Friday, November 14, 2008

The Problem Of Consciousness

The Edge Foundation has posted a video interview with Alva Noë, Professor of Philosophy at UC-Berkeley, on the problem of consciousness. From the Web site:

The Edge Foundation has posted a video interview with Alva Noë, Professor of Philosophy at UC-Berkeley, on the problem of consciousness. From the Web site:The problem of consciousness is understanding how this world is there for us. It shows up in our senses. It shows up in our thoughts. Our feelings and interests and concerns are directed to and embrace this world around us. We think, we feel, the world shows up for us. To me that's the problem of consciousness. That is a real problem that needs to be studied, and it's a special problem.A useful analogy is life. What is life? We can point to all sorts of chemical processes, metabolic processes, reproductive processes that are present where there is life. But we ask, where is the life? You don't say life is a thing inside the organism. The life is this process that the organism is participating in, a process that involves an environmental niche and dynamic selectivity. If you want to find the life, look to the dynamic of the animal's engagement with its world. The life is there. The life is not inside the animal. The life is the way the animal is in the world.

What is at issue is whether we can apply an objective causal model to explain our subjective conscious states to meaningfully explain the mystery of consciousness.

Thursday, November 13, 2008

Public Intellectual 2.0

Daniel Drezner's article on public intellectuals and blogs was recently published in The Chronicle of Higher Education. In this article he bemoans the idea that public intellectuals are no longer in existence. More often than not, the internet is pointed at with an icy finger as the culprit in the demise of the public intellectual. Andrew Keen's book, The Cult of the Amateur: How Today's Internet is Killing Our Culture, is a good example. The general thesis is that good, intelligent commentary and discourse is lost amongst the immature, uneducated masses composing blogs, webpages, and facebook pages. However, the underlying assumption is that traditional media and publishing outlets (books and magazines) are somehow superior and conceal no hidden agenda or bias. Mother Jones is still published in print and the bias is quite obvious.

The argument becomes misguided when the focus becomes the disease of the internet. The real argument should focus on the definition of a public intellectual. As Dezner points out, a public intellectual is someone who writes serious-but-accessible-essays on ideas, culture, and society. I believe most critics forget the public part of public intellectual. When social and intellectual curmudgeons bemoan the lack of public intellectuals they really mean private intellectuals with wider distribution: someone affiliated with a university, publishing in an academic press or journal. However, these works are often written for fellow scholars and the discourse is narrowly focused and inaccessible to the uninitiated. Hence, the public does not read these works (even when the ideas are great and in need of wider dissemination).

The turf war is over intellectual territory. Intellectuals writing for the masses with jargon-free prose but unaffiliated with universities find the internet (blogs in particular) to be the easiest and best form to disseminate their ideas to the masses. Moreover, you don't need a pricey subscription to access the information. Private intellectuals (those affiliated with universities) largely disdain amateurs writing on their topics and won't play on their turf (the internet). Why would they? The history of scholastic publishing is well documented in the university and they hold the monopoly. However, Drezner points out that even academics in the ivory tower have something to gain from blogging:

For academics aspiring to be public intellectuals, blogs allow networks to develop that cross the disciplinary and hierarchical strictures of academe. Provided one can write jargon-free prose, a blog can attract readers from all walks of life — including, most importantly, people beyond the ivory tower. (The distribution of traffic and links in the blogosphere is highly skewed, and academics and magazine writers make up a fair number of the most popular bloggers.) Indeed, because of the informal and accessible nature of the blog format, citizens will tend to view academic bloggers that they encounter online as more accessible than would be the case in a face-to-face interaction, increasing the likelihood of a fruitful exchange of views about culture, criticism, and politics with individuals whom academics might not otherwise meet. Furthermore, as a longtime blogger, I can attest that such interactions permit one to play with ideas in a way that is ill suited for more-academic publishing venues. A blog functions like an intellectual fishing net, catching and preserving the embryonic ideas that merit further time and effort.So what do you think? Do you think the internet (blogs in particular) continues to erode the idea of a public intellectual or does it define him/her?

- JF

Monday, November 10, 2008

Possible Worlds III - Actualism

Lewis held that possible worlds exist exactly like this one. His view entails that there are uncountably many things that exist in "uncountable infinities of donkeys, protons and puddles, of planets very like earth... small wonder if you are reluctant to believe it." Actualist possible worlds tries to use the power of modal logic using actual objects to ground talk of possible worlds. Actualists reject Lewis's view precisely because it is unbelievable.

There are at least three versions of actualist possible worlds semantics. According to Stalnaker, possible worlds are uninstantiated properties. Like the property of being a unicorn, the property exists even if there are no examples of unicorns. In logic-speak, an instance of the property is its instantiation. So uninstantiated properties are properties that nothing has. But for many philosophers, like Plato, the property can exist even if there is no instance.

Alvin Plantinga holds that possible worlds are complete states of affairs. These exist as abstract entities and have properties. The state of affairs "Quine's being a philosopher" has the property of obtaining, while the state of affairs "Quine's being a politician" has the property of not obtaining. Some states of affairs have the property of being possible, and others do not (though Plantinga does not state whether he thinks the imposible states of affairs non-the-less exist). Plantinga has a technical way of defining complete, but basically, for any state of affairs S, a complete state of affairs either includes either S or not S.

According to Robert Adams, possible worlds are not states of affairs, nor abstract objects, but complete, consistent sets of propositions. Propositions are actual intensional abstract entities, and these propositions have the property of being either true or false. A proposition like "Aristotle is tall" contains both the individual Aristotle and the property of being tall. Consistency in complete sets of propositions is inherently modal: It is consistent if it is possible to be true together.

Other philosophers will use a logical notion of consistency, ie, it is consistent iff there is a model which satisfies the set of sentences which mean the propositions. In such a case, anything that is logically consistent is possible, and vise versa. Adams was trying to avoid that conclusion. But the more empiricist philosophers (Hume, Quine, Carnap, early Wittgenstein) all accept that kind of view.

Finally, there are the fictionalists: possible worlds are fictional entities. Just as there are truths about Superman, fiction can ground truth. Just as the fiction of the ideal gas law gives us important truths, so fictional truths can be important. Talk of possibility is grounded on these kinds of important fictions. David Armstrong (not the one at McNeese) holds this kind of view, and cites Wittgenstein as his inspiration.

So possible worlds are: complete consistent states of affairs, complete consistent propositions, complete consistent sets of sentences or made up entities, each version grounding the truth of our modal claims and justifying modal logic.

Wednesday, November 5, 2008

Living History

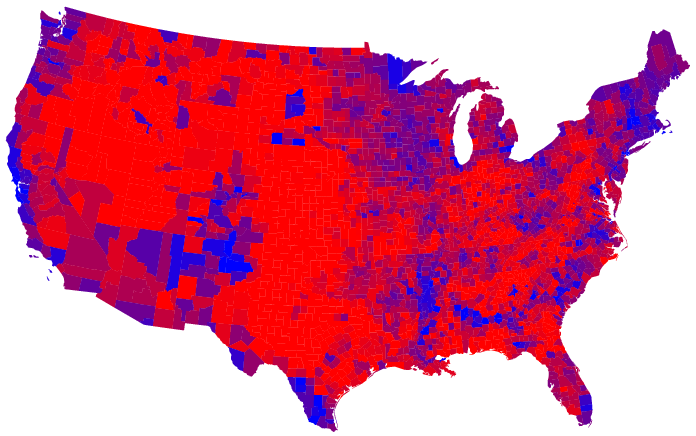

"Tonight's results are historic, and this isn't a platitude. You have witnessed a profound moment in American history - this is a moment that will be more than a historical footnote. Whether you agree with the election's outcome or not, I encourage you to consider the shift that has occurred in society in the past five decades.

Fifty years ago, segregation was enforced and part of mainstream culture. Blacks and whites had separate bathrooms, separate water fountains, separate lives and citizenry. While slavery had been abolished, we were still living the legacy of reconstruction and Jim Crow laws, in which race relations were at a nadir. Lynchings and persecution of minorities were accepted practice in many communities that viewed race as a legitimate reason to denigrate others and relegate them to second class citizenship.

Fifty years ago mixed-race marriages were unacceptable, and "miscegenation" was the cause of scandal in communities. Fifty years ago people were killed for encouraging minorities to vote. Fifty years ago towns would encourage minorities to leave before sundown, so that they wouldn't be killed.

Fifty years later we have elected Barack Obama to the position of President of the United States. Fifty years later we have shown that leadership is not to be identified with race, but by national mandate and governing ideology. Fifty years later we have seen the most significant step in race relations occur in the history of the United States.

This is living history. All too often we identify history with events far in the past, associating the idea with a list of names and dates that we memorize for a test and quickly forget. We ignore the fact that history begins at the end of this sentence. History is not dead - it informs the present and shapes the future. History is one of the most important things we have. This moment will live in history, and I want you to remember it.

Learn from the next four years to see if it is possible for us to overcome the acrimony of the presidential race. Learn from the next four years if it is possible for us to overcome the profound ideological divide that had us at each others' throats. Learn if we can find a common identity as Americans, rather than red states or blue states. This is history you can tell your children, as you experienced it first hand. This is history the likes of which we as a nation have never seen before, and will define our character for the foreseeable future.

I am cancelling class tomorrow - abortion too easily serves the politics of division. I will be on campus and will hold normal office hours, but I will not teach on this issue. We will resume lecture on Monday. Use tomorrow for what purposes seem best to you, but remember that these moments are few, and far between. Use them wisely."

This is my generation's moon landing - an unparalleled event in the history the United States. This represents the best the United States has to offer. This is the kind of event that restores faith in the voting public and is a resounding blow against the politics of division. There are times when I am ashamed for what has been done in the "national interest" and our legal obfuscations attempting to rationalize the most horrific of practices. There are genuinely times when I question whether we, as a nation, have forgotten the political ideals that informed our sense of national identity.

Then there are days like today, when I remember the good that we as a nation can do. From his first words, we have someone seeking optimism and ability. We have someone who recognizes that 50,000,000 isn't a mandate when there are 50,000,000 who voted against him, and recognizes that his political obligation is to all Americans, and not just his base. This makes me proud to be an American, through and through, and the recognition that leadership is not a partisan issue, and that times of need requires a willingness from everyone to assist.

I donated blood with hundreds of others following 9/11. I was part of a line that stretched around the block of people willing to give of themselves when the nation as a whole was attacked. I watched this sense of national identity, of collective existence, wither under puerile criticism and attack over the following seven years. I watched us return to our partisan feelings and sense of schadenfreude when some self-appointed moral paragon revealed himself to be just as human and fallible as the rest of us.

Tonight was the first time in a long time that I felt the same possibility of genuine American identity and mutual support. I hope the next four years is not more of the same. I hope that we use this time to remember that we are a pluralistic nation, not "real Americans" and "fake Americans". I hope we can remember that sense of common identity we realized during 9/11 and its aftermath. I think tonight we've all earned the right to hope.

-MAB

Tuesday, November 4, 2008

V for Voting

Yesterday in the Philosophy club, several people voiced the opinion that early polls were anti-democratic. The argument goes something like this:

If you believe that the candidate you are going to vote for will lose, you are less likely to go vote for your preferred candidate. Polls let people know that their candidate is likely to lose. Therefore, polls make it less likely for you to go vote for your preferred candidate.

This was separated into two separate arguments, first simply polls, and second calling the election (even when right) early, so that people in CA find their votes irrelevant, since the issue is already decided.

If this is right, then in suppressing the vote, polls function anti-democratically.

It must be granted that turnout is lower when you know your candidate will lose. How much lower is very debatable, but excitement about voting leads to higher turnout, and close elections and knowing your going to win lead to excitement, and hence higher turnout. That is why campaigns try to make people excited about voting, flags waving, bands playing, balloons flying, etc.. So let us grant the argument.

The error is in the beginning. People are told they should vote "to make a difference" "so their voice will be heard." This is simply an anti-democratic view. The only time your really make a difference is when your vote is the deciding vote. The will to make a difference is therefore an anti-democratic will, the will to be the one making the decision. The will to be heard is similar, but also misses the basic point in a modern democracy: your voice will never be heard as an individual. You are 1 of 300,000,000 in the country. Your voice as an individual is the squeak of a mouse at a Rolling Stones concert. If you vote to make your voice heard, do not vote, it will never happen. It is the view that your vote must effect something, that your vote must make difference which is the anti-democratic spirit, and suppresses the vote more than anything else. With that view, your vote really does not matter, so why vote?

Now if your voice is part of a choir, a large choir, and the choir is only large when each individual sings her part, then your voice is heard, but not as an individual voice. We hear the choir, not the individual. That is the role of a vote in a modern democracy. And hence polls, or previous outcome, or it already having been decided is irrelevant. Whether the choir you join is the winner or the opposition, you are being heard. And if you have that in mind, the arguments above are beside the point. You vote win or lose, and as you vote, you take your place among the 300,000,000. When you vote, you become a citizen, a part of the body of the United States of America. Isn't that good enough? No, isn't that better than anything else? If you are not content to be one of 300,000,000, then you are not content to be a citizen of this country. It is that simple. And then what would you be content with? Your vote making the difference, your vote deciding, you being the decider... you being the dictator, which will never happen.

So the choice is yours. Do not choose to vote because your candidate will win or lose. Either choose to vote and be an active citizen of this country as it is, or choose not to vote and be a bystander with empty dreams of unachievable anti-democratic power.

Monday, November 3, 2008

Ethical Issues in International Business

Through the Faculty Colloquia series, one faculty member from each of the university's six colleges presents a topic in a specific area of expertise. The presentations are held from 2-4 p.m. on Thursdays throughout both semesters in the Stream Alumni Center and are open free to the public. This informative program is sponsored by the McNeese Alumni Association and the McNeese Write to Excellence Center.

Through the Faculty Colloquia series, one faculty member from each of the university's six colleges presents a topic in a specific area of expertise. The presentations are held from 2-4 p.m. on Thursdays throughout both semesters in the Stream Alumni Center and are open free to the public. This informative program is sponsored by the McNeese Alumni Association and the McNeese Write to Excellence Center.On November 20th, Dr. Cam Caldwell, the director of the Master of Business Administration program at McNeese will give a presentation on the ethical issues in international business.

You can access the rest of the Faculty Collquia series here

Nothing

Exhausted from a trip, so I got nothing today. Will try to have something tomorrow.

Why is it that everyone at funerals and in churches all refer to the people who have died as if everyone knows they are in Heaven, enjoying all of its glories?

Monday, October 27, 2008

V for Violence

I was disturbed by several features of "V for Vendetta." I found the movie to glorify not just violence, but torture. And then it made revolution to be a non-violent wonderful thing (you can't have a Hollywood movie without a happy ending, can you?). But one of the main arguments against revolution is that they are indeed bloody, uncertain, violent and ugly. The romaticization of revolution has a huge effect: it allows for easy justifications. Hence we can look at a functioning society with less freedom we would like (hey, that sounds like ours) and raise start dropping the "R" word, as if its an easy solution to whatever problem. But it isnt. Revolutions are dirty, messy affairs where lots and lots of innocent people get killed, and lots of guilty ones, too. Hobbes knew this well, which is why he was against the whole idea. No, if a movie is to tackle the problem of fascism and revolution, lets have a real look at it, not the Hollywood version. This of course is compounded by celbrating the violence of V himself. And why? Would the violence have been justified if V had not been tortured? If the state had not created the crisis of the bioterrorist attacks? If we just had the all powerful fascist state, but people got there without coersion, would that justify V's violence? (ah, the first interesting question!)

But that was not what I wanted to talk about. Instead, it was the torture of Evey. According to the film, her torture makes her free. Listen to that as I repeat it: through torture, she becomes free. And she becomes free because she doesn't fear death anymore. She is unafraid. OK, let me make this clear: Torture does NOT make people unafraid. It breaks them, and makes them always afraid. Torture does not make people free. It robs them of their humanity. It may make you realize there are worse things than dieing, but that it not necessarily a good thing, and leads to suicide. People at Auschwitz were not free because they realized they would rather throw themselves onto the electric fence than live another day. In short, violence is not a way to overcome existential angst.

Friday, October 24, 2008

Possible Worlds II

First, for most philosophers, all possible worlds are relative to all possible worlds. This has a consequence that it is governed by a formal logical system called S-5. If not all worlds are possible to all possible worlds, then weaker systems of logic govern our inferences. This is precisely what Kripke showed in his published work in the 1950's, when he was 18(!).

It follows in S-5 that anything which is possibly necessary is actually necessary. this has been used to prove God's existence in a version of the Ontological argument. God, if he exists, has the property of being a necessary being. It is possible that there is a God. Therefore, it is possible that a necessary being exists. By S-5, God is actually necessary, and and since anything which is necessary is true, God exists in this world, too.

Other philosophers deny that all possible worlds are possible relative to all possible worlds. Aristotle might not have existed. So there is a world at which there is no Aristotle. At that world, is it possible that Aristotle's son existed? What does it mean to say that some non-existent thing might have existed? In response to these kinds of questions, they deny the universal connection between possible worlds. Worlds in which Aristotle exists are not possible from worlds in which Aristotle does not exist, though the reverse does not hold. If that is right, the logic of modality is not S-5, but something weaker (S-4, for those who are counting) and it no longer follows that just because something is possible that it is necessarily possible, nor does it follow that something that is possibly necessary is actually necessary.

I am looking at my car. It is possible for it to start. But is it necessarily possible for it to start? On one way of looking at things, no, because it is possible for the engine block to be totally ruined. Spelling that out in possible worlds means some possible worlds are not possible from all possible worlds. It is possible that Aristotle exists. But is it necessarily possible? What if human beings never develop? What if the world blew up before humans ever appear on the world stage? Then there would still be a possible world in which Aristotle exists ("Aristotle might have existed" is true), but that world would not be relatively possible from worlds where the world blows up before humans arrive on the scene. Hence we can say Aristotle could not exist if the world blew up before humans arrive on the scene, even though he might exist in other circumstances.

Hope that helps.

I was going to post more on the metaphysics of modality, but ce side tracked me. Blame him. Will try to do that Monday.

Thursday, October 23, 2008

Tuesday, October 21, 2008

Political Philosophy and Human Nature in V for Vendetta

"Political Philosophy and Human Nature in V for Vendetta"

A presentation by Matthew A. Butkus, PhD

Friday, October 24, 2008

2:00 - 5:00 PM

Hardtner 128

Presented by the McNeese State University Philosophy Club

Monday, October 20, 2008

Possible Worlds

On the way out of last weeks meeting, Robert asked me about possible worlds. Todd, Lord Matt and I were using the notion of a possible world in the previous weeks discussion, but we did not say much about them. So here goes:

A possible world is a complete way the world might have been. Suppose you could have been a rock star. Then there is a possible world at which you are in fact a rock star. That part is easy, and gives us a way to think about what might have been. But what are possible worlds?

The first philosopher to use possible worlds was Leibniz, long ago. He used them in part to answer the problem of evil: This is "the best of all possible worlds" and hence a good God would naturally chose this one to being into existence. For Leibniz, possible worlds were ideas in the mind of God. Imagine Him going through each of the ways the world might have been. When he finally reaches the best of all of them, he chooses to make that one real. Philosophers call that "actualizing" or "instantiating" that world. So this is the only real world, but the others exist as ideas in the mind of God. When you say "I could have been a rock star" you are saying that there is an idea in the mind of God, and in that idea, you are a rock star. Unfortunately, that world was not the best of all possible worlds, and hence you are actually stuck with only dreams.

Possible worlds lay dormant as a philosophical tool until revived by Saul Kripke in the 1950's and 60's. In order to deal with a difficult problem in Modal Logic (defining validity, and hence providing a semantics, for those curious), he reintroduced the notion of a possible world. Pressed later on their metaphysical stauts, Kripke said that a possible world simply was a counterfactual situation. A counterfactual is a conditional (if-then claim) where the antecedent is false. Example: If Germany had won the war, blah blah blah. That stipulates a possible world where Germany did win the war. On his view, these do not exist as ideas in the mind of God, or any where else. However, if possible worlds do not exist, in what way do they make modal claims true?

Enter David Lewis. Lewis (and I'm not making this up) was reading a work of science fiction in which someone creates a new invention which allows people to travel to other possible worlds. Inspired by this, Lewis defends what he calls "Modal Realism," the view that other possible worlds exist exactly like this one, just in a different space-time. Real people, real situations. What happens in those other worlds makes our claim about what might have been true. Our world is the actual world for us, but our world is a possible world for them, and their world is their actual world. For anything that you think might have been, there is a world, which exists just like this one, where that actually happened.

Actualism is the view that the only thing that exists is the actual world, and actualists reject Lewis's views. More next week, if there is any interest.

Tuesday, October 14, 2008

JONATHAN MILLER'S BRIEF HISTORY OF DISBELIEF

Shadows of Doubt

Jonathan Miller visits the absent Twin Towers to consider the religious implications of 9/11 and meets Arthur Miller and the philosopher Colin McGinn. He searches for evidence of the first 'unbelievers' in Ancient Greece and examines some of the modern theories around why people have always tended to believe in mythology and magic.

Noughts and Crosses

With the domination of Christianity from 500 AD, Jonathan Miller wonders how disbelief began to re-emerge in the 15th and 16th centuries. He discovers that division within the Church played a more powerful role than the scientific discoveries of the period. He also visits Paris, the home of the 18th century atheist, Baron D'Holbach, and shows how politically dangerous it was to undermine the religious faith of the masses.

The Final Hour

The history of disbelief continues with the ideas of self-taught philosopher Thomas Paine, the revolutionary studies of geology and the evolutionary theories of Darwin. Jonathan Miller looks at the Freudian view that religion is a 'thought disorder'. He also examines his motivation behind making the series touching on the issues of death and the religious fanaticism of the 21st century.

On Humility

I did promise to have a new post each Monday. I failed. Sue me.

Last week, we engaged had a discussion about humility. What is humility? Is it a virtue or a vice? Are people being humble when they give glory to God?

Normally, you cannot do philosophy by dictionary. A dictionary definition tells us how we use words, and there is no truth that is uncovered by simply showing how we use a word. moreover, people may use a word in one way, but the philosophical impact of the concept may lie in a different place. Be all that as it may, I find it useful in the present circumstance to think about the dictionary definition. To be humble is to have a low estimate of one's importance. The other connections we were making to humility seem to follow loosely from this definition.

Hence giving glory to God is an act of humility in a way: you are saying I did nothing, it was all God's doing, which is why He gets the glory, not me. But 1) most people who say this are basking in the glory while saying it. Then it becomes at best an empty gesture, even if in some sense heartfelt. 2) Conceiving of yourself as the instrument of God's will is not humility. True, he could have used someone else as his instrument. But that only marginally lowers the importance of the actor. In fact, conceiving of yourself as the instrument of God raises your importance in another way: you are like a prophet! God choose you! Your god given talents make you special, and special in a divine way, as it is God's power that you have and use. Being God's tool makes you almost divine. Giving God the glory is false humility.

Nietzsche criticizes humility for two reasons. The first is that we value humility not because it is good to be humble, but because lack of humility makes unimportant people feel bad about themselves, and creates rage and depression amongst them. Even if true, saying "I am smarter, stronger, faster, prettier than you" makes other people feel bad, rocks the boat, offends the herd. Valuing "I am worthless, unimportant" is the value scheme of the slave.

The second criticism he makes is far deeper: Valuing claims like "I am worthless" strips life itself of value. To live, to value life, you must think positively of this life. The humble monk, sitting in his hut, does not live life, he denies it, denies life has value. The monk does this for a variety of reasons, but the main Christian one is to see this life as a punishment for our sins. If so, reveling in life is reveling in our punishment, turning it from punishment to reward. Humility is essential to thinking of this life as a punishment. Humility is thus life-denying.

So is that right? And even if it is right, are there true virtues to humility? If so, what?

Sunday, October 5, 2008

Function and Sex

As I'm grading several papers on Aristotle's function argument, it occurs to me that we take the basics of his argument very seriously in a variety of contexts, and always assume the basic Greek worldview. It was basic to the Greek way of thinking that every thing, every species, every action has a unique function. Aristotle and others then use knowledge of that unique function to determine what a good instance of that thing may be. Many people still use the basics of that view when it comes to sex, and this has profound implications for the ethics of sex. But the assumption seems flat out wrong, and hence the ethics based on the function argument seems poor at best.

Aristotle argued that the word good is always contextual, getting its meaning from the noun it modified, and the noun gets its meaning by its particular function. So, a pianist is someone that plays the piano, and a good pianist is one that plays the piano well. When you find the unique function of an object, you can then understand what a "good" object maybe, be it a piano player, or a car.

He argued that the function of man is not mere nutrition and growth, because these attributes are shared with plants, and so are not man's unique function. He argued that sense perception and movement are not man's function, because these are shared with animals. Man's unique function is the use of reason, hence the function of man is to reason, and a good man reason's well, both in practical life as well as in the contemplative life.

The immediate effect of the argument is to place an emphasis on reason, and on the unique characteristics of man, separating him from being an animal. Hence those features of human existence that we share with animals are downgraded, and acting like animals is a bad thing. And if its a bad thing, then anything which takes us away from our rational, human nature is degrading and very bad.

If this argument is not right, then it is very easy to see why some philosophers (like Kant) holds that sex is inherently degrading, reducing us to animals, and hence morally reprehensible. Sex might be necessary to keep the species going, but not good in itself, not to be valued as anything except useful for procreation. (Of course it follows that if sex is valuable for its unique function, and the only function it has that is truly unique is procreation, that good sex is reproductive sex. You may think you have had good sex before, but if it did not produce offspring, you are wrong. And you might have thought that sex that cause a child was not all that, but again, you would be wrong. The best sex, according to this argument, is one where a child is conceived.)

We might grant that procreation is the only unique function sex has, but it is obvious sex has many other functions that are not unique. You might think, for example, that it brings couples closer. Everyone must grant other actions can do that as well, so it is not the unique function, but few can deny that it can also have that effect as well.

Here, then, is the question: Why would the obvious uniqueness of one function make the others irrelevant, or even elevate the unique function? Why is value tied to the unique function? Why cannot we attach meaning and hence value to any purpose we give to any act or person? Then, no longer accepting to split between animal and human, as we no longer accept the function argument, we need no longer look at our animalistic nature with horror and dread. Deny that the only function which counts is the unique function, and off we go with a very different conception of value and ethics. So what justifies the assumption either that function is unique or that only the unique function is the one that counts?

Thursday, October 2, 2008

Monday, September 29, 2008

Battlestar Gallactica and Philosophy

I had a professor at the University of Texas who taught a course called "Philosophy and Literature," which I mistakenly thought would be about, uh, literature. Instead Nick Asher (famed logician and philosopher, good guy, too) used science fiction as the backdrop for philosophical thought. We read Dune, Nueromancer, some David Brin, etc.. [Interesting side note: Nick wrote me a letter of recommendation for graduate school based on that one course, and the papers I wrote for him. I went to see him to make sure the letter writing was going okay, and he told me that he was having a little difficulty, given the course, in not sounding totally out of his mind as he described my work.]

Lord Matt has been trying to get me to watch the new Battlestar Gallactica series on DVD, and claimed there was much philosophy contained therein. Still not sure what he had in mind (although I do think some classic philosophy of mind questions are at work... unfortunately, that's not my cup of tea.) But lately one theme has struck me.

In the first season, the civilian authority and the military authority come to an agreement, splitting sovereignty by granting him control of military matters, and her authority over all others. No big deal is made of that agreement, but in the second season, trouble brews as the President urges a member of the military to not pay attention to her orders, compromise her mission, and complete a task the military commander has already rejected. The officer does what the President asks, which then prompts the military commander to suspend, arrest and jail the "President," amid questions of legitimacy. This provokes a civil war (though a one sided civil war, as the military has full control of, uh, the military.) Some people support the President, others the Military leader. Sides are drawn up, and chaos is about to reign.

Hobbes, in his classic Leviathan, argued against splitting sovereignty (giving one person or group of people authority over one area, and another over another) for precisely the same reason in 1651. He argued that the purpose of sovereign authority was to get people out of the state of war by making fear of other people irrational. But splitting sovereignty sets up a situation which makes it easy for people to rationally justify civil war, and hence plunging the community into the very state the establishment of government was meant to avoid. In his day, sovereignty was split between the King and Parliament, and when they came to a clash on some point of controversy, the result was the English Civil Wars.

Hobbes writes:

"A kingdom divided in itself cannot stand: For unless this division proceed, division into opposite armies can never happen. If there had not first been an opinion received of the greatest part of England, that these powers were divided between the King, and the Lords and House of Commons, the people had never been divided, and fallen into this Civil War;"Of course, BSG then blows it by healing the rift without any attempt to solve the problem. The two leaders just look at each other and start working together.

Thursday, September 25, 2008

Information regarding philosophy majors, concentrations, etc., etc.

I talked with Ray Miles yesterday, and he provided me with some information regarding getting the philosophy major up and running. He stressed that this is a long process, and it is entirely possible that (depending on what year you are), you may not still be a student here by the time it is official.

That being said, there are a number of things that need to happen in the meantime. Hanno and I had a discussion regarding potential concentrations to attach to existing majors, and I'll be running a few ideas past Todd, too, in order to maximize the availability of philosophy to McNeese students (e.g., attaching a bioethics concentration to the nursin curriculum, or a generalized philosophy concentration applicable to most majors).

So, what is this "concentration" I've mentioned? It's a minor in philosophy. Kinda. The only real difference is the number of syllables, and that because Louisiana is goofy, you can't officially have a minor without a major. A concentration requires 18 credits, but allows us flexibility in development (i.e., we can decide what will constitute the core courses, and what will constitute electives).

The philosophy faculty will be sitting down at some point to hammer out the finer points, but I thought it would be useful to get feedback from you all, too. I'm thinking that we can discuss this on Monday (and this will be a good meeting to bring all of your friends who are interested in philosophy, as this will be our best chance to gauge student interests). I am also happy to print out the recommendations from the American Philosophical Association regarding the recommended core elements of a philosophy curriculum. Additionally, I will be putting together a quick anonymous survey regarding a major to foist upon all of my students (with an incentive for completing it), which will give us some qualitative and quantitative data we can peruse.

In regards to getting an actual major up and running, Ray advised letter writing (Hanno and I had talked about petitions, but Ray suggested that they would be functionally meaningless). It isn't enough to write a letter just saying you want a philosophy major; the letter should contain what you plan to do with a philosophy major (e.g., "it will help me with my plans for law school, graduate school, etc., and here's how"). I have data on the extraordinary success philosophy majors have had on standardized exams like the GRE, MCAT, LSAT, etc., and I'm happy to send anyone information on that (we consistently outperform almost every other major and discipline; contact me at mbutkus@mcneese.edu), as well as testimonials from individuals in a number of professions describing how the philosophy major has helped them. I have several of these posted outside of my office (222-M Kaufman Hall). These letters can go to a number of people (and, in fact, I would suggest sending individualized copies to all of them):

Dr. Jeanne Daboval (Vice President of Academic Affairs)

Dr. Ray Miles (Dean, College of Liberal Arts)

Dr. Billy Turner (Dept. Head, Social Sciences)

It would be good for us (the philosophy faculty) to maintain hard copies of these letters, too, as a record of student interest. I'm happy to donate a drawer in my filing cabinet.

Additionally, Ray recommended getting letters from the outside community (e.g., professionals outside of McNeese who have benefitted from studying/majoring in philosophy) to demonstrate applicability and practicality of the major. Philosophy majors pop up in a number of expected and unexpected places - I'd suggest checking law firms to start.

Anyway, we can discuss all of this at the meeting. I can't emphasize enough how important it will be to show large student interest, both in the philosophy club as well as the philosophy major. So, bring friends, friends of friends, shanghai random students and drag them along, etc.

-Matthew Butkus, PhD

Monday, September 22, 2008

The Real Difference Between Liberals and Conservatives

Jonathan Haidt, a psychologist from the University of Virginia, provides a compelling argument about moral psychology and the political mind. According to Haidt, there are five psychological systems that provide the foundations for the world's many moralities.

The five foundations are:

1.) harm/care

2.) fairness/reciprocity

3.) ingroup/loyalty

4.) authority/respect

5.) purity/sanctity.

Haidt makes the case that political liberals have moral intuitions primarily based upon the first two foundations. Political conservatives, on the other hand, have moral intuitions primarily based upon all five foundations.

Does this adequately describe you? As a conservative? As a liberal? Given this rubric, where do you think political "others" fall on this spectrum?

You can watch Haidt's presentation here.

Call For Papers and External Reviewers

Stance: An International Undergraduate Philosophy Journal

Submission Guidelines:

Stance welcomes papers concerning any philosophical topic. Current undergraduates may submit papers between 1500 and 3500 words in length (exclusive of notes and bibliography). Papers should avoid unnecessary technicality and strive to be accessible to the widest possible audience without sacrificing clarity or rigor. They are evaluated on the following criteria: depth of inquiry, quality of research, creativity, lucidity, and originality. For more specific guidelines see the website.

Submission Procedures:

• Manuscripts should be in Microsoft Word format and sent as an attachment to stance@bsu.edu

• Manuscripts should be double spaced (including quotations, excerpts, and footnotes)

• The right margin should not be justified

• To facilitate our anonymous review process, submissions are to be prepared for blind review. Include a cover page with the author’s name, affiliation, title, and email address. Papers, including footnotes, should have no other identifying markers.

• Footnotes should use the author-date format found in The Chicago Manual of Style.

• Please use American spellings and punctuation, except when directly quoting a source that has followed British style.

VISIT STANCE ON THE WEB AT HTTP://STANCE.IWEB.BSU.EDU/

Deadline: Friday, December 19, 2008

Call for External Reviewers

Stance: An International Undergraduate Philosophy Journal

Stance is looking for interested undergraduate philosophy students to serve as external reviewers for this year’s issue. This is an exciting opportunity to gain experience working for a groundbreaking journal in the field of philosophy, as well as a chance to hone your skills in writing and reviewing philosophy papers.

Participation in this project will require a moderate level of experience in philosophy, strengths in writing and editing, as well as a sufficient degree of self-motivation necessary to complete the work by the given deadlines. We anticipate that each external reviewer will be sent one or two papers to review in late December or early January. It is possible that a reviewer will be asked to review one or two further submissions later in the spring if a particular piece requires further consideration. If accepted as an external reviewer, training material will be provided that will explain what is expected in the formal review. Reviewers will also be credited in both the print and electronic versions of the journal.

If you are interested, please provide us with the following information:

Name:

Name of School:

Year in School:

Major(s)/Minor(s):

Philosophy Courses Taken:

Your specialty, or concentration

What experience do you have that would qualify you for this project?

What goals do you have that working on Stance will support?

What, in your opinion, are the makings of a good philosophy paper?

Along with this application, we have provided a further application form to serve as a letter of recommendation from a philosophy professor with whom you have worked. Please have both items returned to us by e-mail at STANCE@bsu.edu or by mail at:

Stance

Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies

Ball State University

Muncie, Indiana 47306-0500

Postmarked By: November 3

Thursday, September 11, 2008

Pre-Game Coin Toss Makes Jaguars Realize Randomness Of Life

At the last philosophy club, some of you expressed interested in professor Furman offering Existentialism as a philosophy course in the future (I am looking at you Mike Chavez). A few of you have already encountered existential philosophers in a previous course (Sartre or Camus, for example). However, some of you probably have not. As the humorous Onion video suggests, existentialism is a philosophy that emphasizes the uniqueness and isolation of the individual experience in a hostile or indifferent universe. As a corollary, individuals create the meaning for their lives.

How does this idea strike you? Do you believe life is basically meaningless and random? Moreover, does this randomness suggest that people are entirely free and thus responsible for their actions? On the other hand, does this randomness suggest that our actions are futile and nothing else matters (as Metallica would say)? Some suggest that Camus ultimately answered this question by purposefully crashing his car on January 4, 1960...thus ending his life.

Monday, September 8, 2008

Knowledge and Necessary Truth

Most people grant that the following claim is true: If I know P, then P must be true, or alternatively, then necessarily P. What is the meaning of the consequent? There are at least three. The claim could assert the certainty of P, given that P is known. The sentence would then read: If I know that P, then P is certain. This seems perfectly fine.

But there is an alternative meaning: that knowing P implies the necessity of P. A claim is necessary if it is impossible for it to be false. There are two kinds of necessary truths. The first are made true by virtue of the meaning of the terms involved. These truths are called "De Dicto," and examples are "Bachelors are unmarried," and "Unicorns have one horn." These are frequently called "analytic truths," following Kant. The other kinds of necessary truths are more controversial. These are called "De Re," and are somehow necessary in virtue of the object itself, and not merely the description. If there is no de re necessity, then all non-analytic truths are not necessarily true. Primary examples of de re necessity: Gold has 79 protons, gold is atomic. These are not analytic because they were discoveries, and analytic truths are not. If true, they are necessarily true. But we could be wrong, we might have made an error in discovery.

Be that as it may, there are several examples of claims that are not necessary. "Hanno exists," "Hanno's phone number is 555-1212." Notice then what happens. If the initial claim is true, then the claim "If I know Hanno exists, then necessarily, Hanno exists." Well, I do know that Hanno exists. It follows that Hanno necessarily exists. That cannot be right, since my existence is surely contingent on many factors. Just because I know my phone number does not mean I could not have had another, or no phone number at all.

Now, if the second reading of the initial claim were right, knowledge all by itself would imply the necessity of everything known. If some being knew everything, then everything would be necessary. But knowledge by itself does not imply the metaphysical necessity of everything, but merely the epistemic necessity (certainty).

But if we follow the grammar of the initial claim, we can see the error. The necessity does not apply to the proposition, but to the implication. The third way of reading the initial claim is: It follows necessarily that if I know P, then P. This is not a claim about certainty, nor is it a claim about the necessity of P. It is a claim about the necessity of the connection between the antecedent and the consequent, between "I know P" and P. On this reading, I can know Hanno exists, and grant the first claim. But what follows is merely that Hanno exists. My existence is no longer necessary, and the rest of the world can breath a sigh of relief.

It then follows that even if some being knows everything, it does not follow that everything that happens happens necessarily. That may still be true, but it does not follow merely from the state of knowledge.

Friday, September 5, 2008

Is Paying For Music Wrong?

Merely by posing the question in that form, the author has already conceded to his opponents the bulk what they themselves have to proof; namely, that "file-sharing" is stealing. By making this concession, the burden now falls upon the author to make a moral justification for "theft."

Not that this burden is insurmountable. Even within traditional approaches to ethics there are weighty moral arguments for "theft" of specific objects from specific persons under specific conditions. Those arguments invariably rest upon conditions of the material or social value of the pilfered item, the proportionate distribution of property between the thief and the victim of theft, the frequency of theft or immediacy of need, and (most importantly) the issue of life or health (e.g., the peasant stealing a sack of wheat from a wealthy nobleman to feed his starving family). This example should illustrate the problem a defender of file-sharing would face availing herself to this exception, given that it would strain the imagination to conceive of a case where downloading music, movies, games, etc. would serve immediate vital needs. To make a moral case for the "stealing" of copyrighted media, the file-sharing advocate really has no recourse to the limit cases of traditional ethics.

Let's be clear that the question “Is stealing music wrong?” is a moral and not a legal (in the sense of "positive law") one. Any group of bureaucrats can, with the fiat of the courts, define what constitutes "stealing." What we are aiming at is the essence of what it means "to steal."

Let's look at "stealing." Granting that there is a synonymous relationship between the verb "to steal" and the noun form "theft" such that we can substitute (mutatis mutandis) one concept for the other, we can avail ourselves to to Merriam-Webster, which defines "theft" as “the act of stealing; specifically: the felonious taking and removing of personal property with intent to deprive the rightful owner of it.” Let's examine what is covered in the "specifically" clause by way of an example:

Now, let's draw our attention to the two words: "removing" and "deprive." Take a second example:

It is unfortunate that such circumstances seldom obtain in nature. Because of the limitations of material objects, most things can only be used by one or a few persons at a given time, exist in limited quantities, or for a limited duration. Those things that have been perceived to be free and of an unlimited supply have been recognized by almost all pre-industrial cultures as available to everyone in the community to use as they see fit, providing their use neither diminishes the same ability for others or in some way imposes limits upon the supply available for the community. This is what has traditionally been referred to in English, "the Commons." The notion of the commons was always applied to material things whose very existence could be jeopardized through its use.

Wouldn't it be great if there were some aspect of reality that did not suffer from these material limitations? That we could somehow have at our disposal, that we could in some way take possession of without depriving others of the same possession? Or that we could reproduce an infinite number of times without diminishing resources upon which it is made?

If Jack approaches Jill and asks for her bucket, Jill has two choices: she can either give him the bucket or not. "To give" means to relinquish your possession of a thing. If Jack & Jill come to an agreement where Jack can use the bucket for a designated period of time, and then he returns it to Jill for a period of time, and back and forth, we usually call this "sharing." But it is only "sharing" in an analogous sense, since at any given time only one of them have possession of the bucket, and the other one doesn't. With physical things, we often use the term "sharing" in this restricted sense: “I am sharing a bench” or “I am sharing my ice cream.” But in both cases what you are doing is relinquishing (giving) a portion of your possession to another.

What makes so-called "intellectual property" different from real property is that it does not suffer from the limitations of materiality described above. What the "intellectual" designates is that it is based on ideas rather than physical matter. Ideas need only a base set of experiences to be duplicated. If Jill shows Jack how to make a bucket, Jack "possesses" the knowledge of making a bucket to the same degree as Jill, without depriving Jill of her own knowledge of bucket-making. Jack might still need some tin to make a bucket, but by being taught by Jill how to make a bucket, he now has the knowledge of bucket-building. The means by which ideas are duplicated is by experience. Anyone who sees, hears, tastes, etc. can potentially duplicate the idea. Ideas can be "given" is such a way that the giver doesn't relinquish possession of what is given. If you have an idea, as soon as you share that idea with others, they have full possession of the idea as well. This is "sharing" in the fullest sense. Additionally, when an idea is shared with others, that idea becomes the building block for new ideas and new applications of that idea.

In an altruistic society (that is to say, a healthy society) the question of ownership would only arise in those circumstances where the materiality of property prevents the equal access by two or more parties. The notion that "theft" would apply to something which two or more parties can have equal access to is not only an absurity, but the questionable party in such a disagreement would be the one who seeks to make a claim of ownership to what could easily be accessible to all.

If, instead of making buckets, Jill composed a song, by hearing & remembering to a sufficient degree to recite the song, Jack now also possesses the knowledge of this song. Jill has a legitimate claim to being the composer of the song, but only way Jill can prevent Jack from reciting the song (if she can't convince him not to) is under the treat of violence. It is only by instituing a system of violence that anyone can effectively convince others of their society to pay for something that is naturally accessible to all.

Monday, August 25, 2008

Is Stealing Music Wrong?